For decades, Body Mass Index (BMI) has been used as the go-to tool for labeling people as underweight, healthy, overweight, or obese. But here’s the problem: this measurement was originally developed using studies of white populations. That means it doesn’t always paint an accurate picture for people of color—and it may even do more harm than good.

Table of Contents

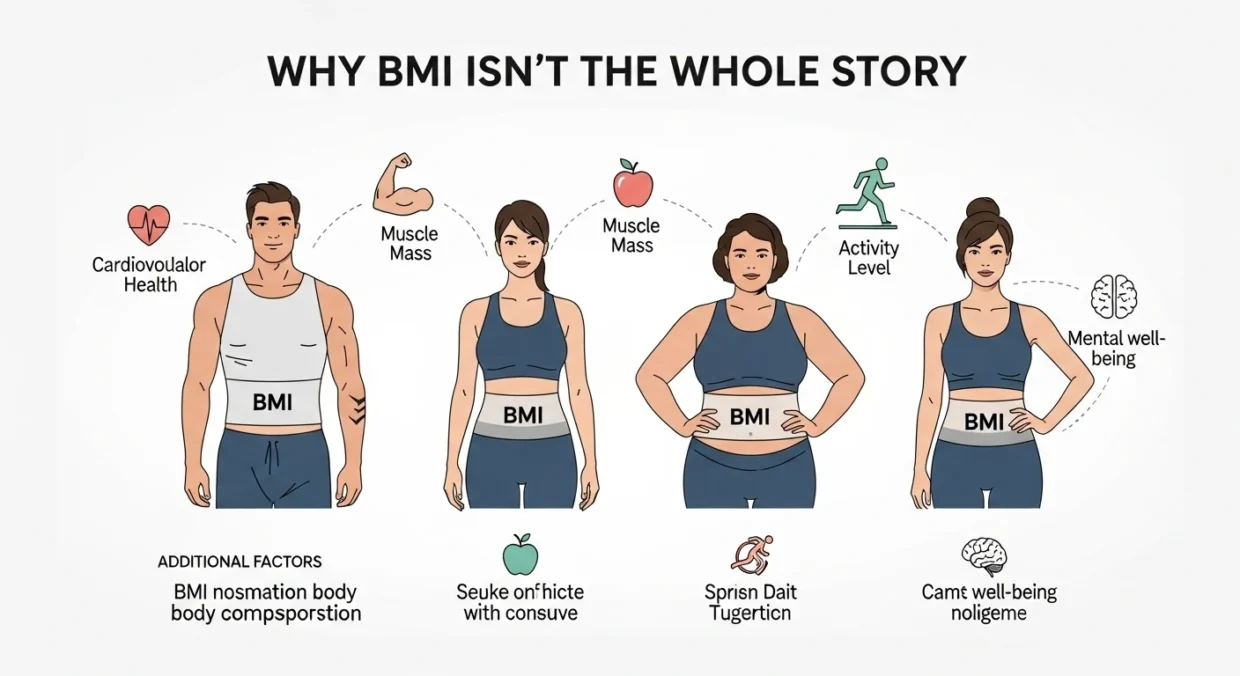

Why BMI Isn’t the Whole Story

At its core, BMI is a simple formula comparing weight to height. While it’s often used as a quick estimate of body fat, it ignores important factors like body composition—how much of your weight is fat versus muscle.

This oversight can be misleading. For example:

- Athletes or anyone with higher muscle mass are often flagged as “overweight,” even when their body fat is perfectly healthy.

- Non-Hispanic Black men and women typically have lower body fat and higher muscle mass compared to white and Hispanic individuals. As a result, BMI may unfairly classify them as overweight or obese.

So, while BMI can be useful for tracking trends in populations, it shouldn’t be the sole tool to diagnose obesity in individuals.

How BMI Plays Out Across Different Ethnic Groups

- Black, White, and Hispanic populations: BMI is applied the same way across these groups, even though their body compositions differ.

- Asian populations: Adjustments have been made because BMI often underestimates obesity here. Many Asians may have a “normal” BMI but still carry higher body fat levels, which increases their risk for type 2 diabetes.

- Inuit populations: Older studies suggest BMI tends to overestimate obesity among Greenland Inuit compared to white Europeans and Americans.

For Black women in particular, differences in body structure may be part of the reason BMI rates appear higher—but more research is needed to see what this means for long-term health.

The Role of Racism in BMI

Here’s where things get even more complicated: structural racism plays a big part in BMI statistics.

Studies in U.S. counties show that discriminatory policies and unequal access to healthcare directly impact health outcomes—and contribute to higher BMIs among Black populations.

In fact, data reveals:

- White men have the lowest weight gain trajectories.

- Black women have the highest risk of developing obesity and average BMIs about 6% higher than other groups.

Because BMI was designed using white populations and doesn’t account for ethnic differences, many experts now call the metric inherently biased—even racist.

Read About:Say Goodbye to Belly Fat After 40 – Here’s the Real Way to Get Fit (No Gimmicks!)

Better Alternatives to BMI for Black Women

If BMI can be misleading, what else can we use? Thankfully, there are more accurate tools to assess health risk, especially for Black women:

1. Waist Circumference

- A strong predictor of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

- Traditional guidelines: less than 35 inches (88 cm) for women and less than 40 inches (102 cm) for men.

- Ethnic-specific recommendations are being developed for even greater accuracy.

2. Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR)

- Looks at how fat is distributed across the body.

- Strongly linked to heart disease and metabolic risk.

- WHO suggests an ideal WHR of less than 0.85 for women and 0.9 for men.

3. Body Impedance Analysis (BIA)

- Offers detailed insight into body composition.

- In population studies, it can sometimes be used in place of advanced scans like DXA (the “gold standard”).

The Bottom Line

BMI may be quick and convenient, but it’s far from perfect—especially for Black women and other ethnic groups with different body compositions.

Here’s what we know:

- Black people often have more muscle and less fat at a given BMI.

- Structural racism also plays a role in higher BMI numbers for Black women.

- Using BMI alone can lead to misclassification, stigma, and even unfair treatment in healthcare.

The takeaway? BMI should never be the only measure of health. Tools like waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body impedance analysis provide a much clearer picture. For Black women especially, relying solely on BMI isn’t just inaccurate—it may be downright unfair.